The feeling of disorientation is a rare experience for New York City, and Central Park is one of the few places where you would find it.

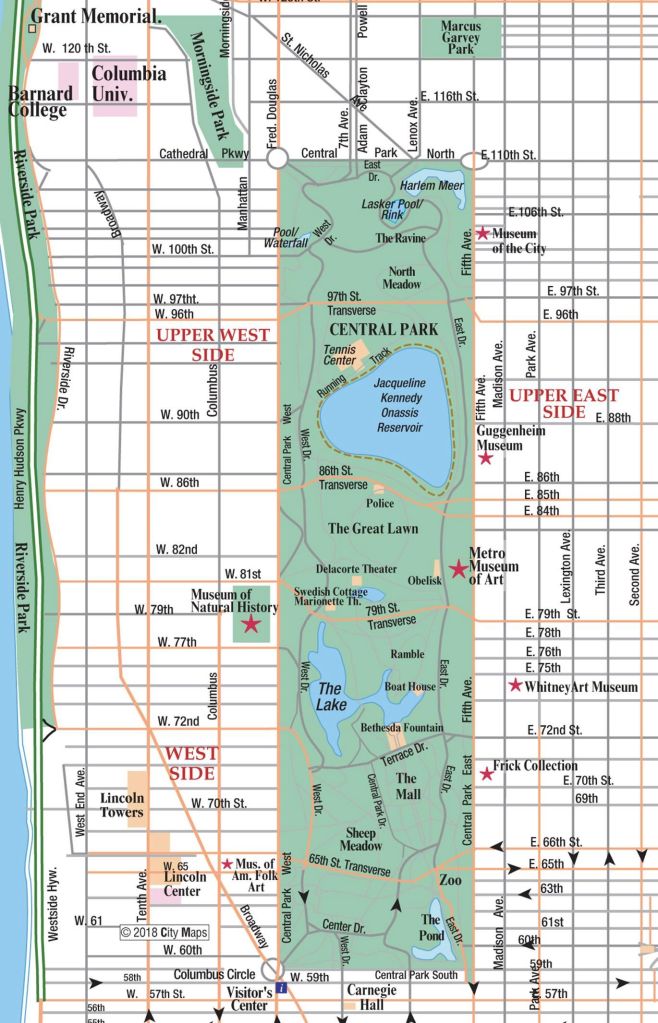

Recently, as I started running in Central Park, the sense of disorientation has become stronger than ever. I would usually start my run at the 77th street entrance on the west side of the park and follow the path to the Reservoir located on 86th, where I would then continue around the reservoir counterclockwise. Almost immediately upon entering the park, I would be plunged into the canopy of trees thick with leaves, which would soon start to block the buildings, eliminating any difference between the park and some nameless trial in the Bear Mountains. Before long, however, I would reach the entrance of the reservoir trail. The view is stunning: a row of pre-war buildings juxtaposed along the Fifth Avenue would manifest themselves first, their white or light yellow facades glimmering under the afternoon sun–how stunning the view must be looking out of their windows at the park! By then, I would have barely begun to exhaust my stamina and thus still capable of enjoying the view and breeze as I run. It is also at this point that I would experience the sense of disorientation for the first time, as the buildings are laid before my eyes in a peculiar angle utterly different than that formed as one wanders within the city’s streets. Before long, my joints would start to burn with my breath becoming heavier. These symptoms would usually amount to the decision to take a short break at the first brownstone building I see along the trail, which I have remembered well since my first visit to Central Park six years ago (the building, which herald the approach of the stunning view of the reservoir, would, whenever I enter the park from the east side, make my heart beat like that of a traveller who glimpses on some low-lying ground a stranded boat, and cries out, although he has not yet caught sight of it, “The Sea!”). It looks rather like a military outpost, albeit windowless, with ‘1884’ carved above its frieze (I never stopped wondering what the date means, perhaps the time it was constructed?). Although I’ve never seen anyone entering or exiting the building (after all, where are the doors?), its existence is by no means meaningless, at least to the runners, since the two of them along the reservoir trial can be conveniently used as markers for the progress of one’s run and on top of that, as in my case, water supply stations.

Passing the ‘outpost’, I would enter a straight path stretching northward for about ten blocks. The sense of orientation that has been disrupted by the winding trail immediately returns, and the view regains its order as its relative position in space with regard to the streets and avenues of Manhattan become once again imaginable. The buildings on the Upper West Side would stretch indefinitely into both directions, almost mirroring those on the East Side a few moments ago. The sense of order, however, is inevitably accompanied by a sense of boredom, which, even the occasional glimpse of the beautiful twin towers of ‘El Dorado’ is incapable of fully taming. Finally, the turn of the trail would become visible, leading to a second ‘outpost’ looming behind the trees, and I would once again be able to locate myself within my run. Feeling increasingly exhausted, I would aim the second ‘outpost’ as my temporary destination, before which, I would first reach the north side of the reservoir, where the view is more unobscured than ever. The ‘millionaire row’ of the 58th street would manifest itself before me, with the iconic 432 Park Avenue, Steinway and Central Park towers penetrating into the clouds, leaving an almost equally sharp reflection onto the water, like the cloud-piercing blocks I stubbornly stacked to build in Minecraft. In the meantime, the buildings of the Upper East Side and Central Park South, apparently connected by the trees below them, would merge into one row of buildings to fill up one’s horizon, as if they are not in fact separated by a 90-degree angle, with their joint identifiable only by the sudden transition in architectural style. Without a clear sense of where the streets and avenues are, I would once again lose my sense of orientation, often to a greater degree than the first time.

This uncanny feeling would continue through the rest of my journey, along the remaining contour of the reservoir, and would indeed be exacerbated as I peek through the trees at the buildings’ facades, expecting them to be perfectly parallel to the direction I am heading but finding it pointing altogether to another.

These feelings of disorientation reminds me of Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology of perception, which points out that as we perceive objects, we are not just viewing it from our everyday perspective, as dictated by our eyes, our distancing to the object, etc., but we are also, in the back of our mind, engaged in an infinite number of vague perceptions from the angles from which the object might be observed and approached. To me, New York City, or more precisely, the map of Manhattan is such a frame of reference. Having lived in the city for a certain period of time, one gets accustomed to locating things in terms of their “coordinates” on the “chessboard”–for example, when I tell my friend to meet at ‘that McDonald’s on West 4th and 6th Ave’. As a result, one unconsciously modifies their mental map to accommodate the city’s layout and gradually form the expectation that only two possible setups are possible for the buildings relative to the direction one’s heading–either completely parallel, or completely perpendicular. These implicit assumptions and expectations are robust to most “unorthodox” neighborhoods of Manhattan, as the order of the chessboard remains salient as long as the ‘regular’ buildings remain visible. However, these expectations are completely overthrown as one enters Central Park, where no trace of these regularities can be found. Hence the sense of disorientation.